If you really don’t like math, skip this one. Before long I’ll have a post on randomness, free will, cryptography and determinism—which are pretty math-y things, I know, but I promise there will be little-to-no actual math!—and I hope to catch you then.

If, on the other hand, you fall into any of the following categories, I urge you to continue:

You believe in the “Self-Indicating Assumption” (SIA)

You believe in the “1/3” answer to the Sleeping Beauty problem

You enjoy tackling probability puzzles

Or you simply enjoy reading about them

I start off with a couple of famous paradoxes in my first section—at least check those out!

For those of you in the first two categories, my goal with this post is not to disprove anything to you. My goal is to give you the tools to disprove the SIA or the “1/3” SB answer for yourself. (Part of the reason for this: I’m not actually sure if the SIA is well-defined enough to be either proven or disproven; if different readers take different approaches to the SIA, maybe one of those approaches will actually be valid, and if so I want to know.)

If you’re just here for the ride, I hope my problems will be interesting, teasing out different sorts of probabilistic intuitions, and also potentially able to highlight flaws in mathematical reasoning that you might have.

If you manage to answer all of the following problems correctly on first try, then kudos!

For everyone else: Good luck, or happy reading.

Boy or Girl

The Boy or Girl paradox, also known as the Two Children Problem, was first posed by Martin Gardner in 1959 in a column of Scientific American. The question proved a popular and enduring one.

For instance: According to Guinness, the person with the highest IQ ever recorded is currently Marilyn vos Savant. (Her being a “savant”, and her name being the same, is a coincidence; though a French word, Marilyn inherited the name from both her maternal grandmother and her maternal grandfather, both of whom hailed from a small town in Northwestern Italy.) She was a famous columnist (I say “was” because it appears she hasn’t written any stories since 2022, nor posted any “Numbrix” challenges since 2024) who responded to readers about the Boy or Girl paradox more than once during the 90’s, and even polled her readers (receiving 17,946 responses!) to prove an answer.

The paradox can be phrased in different ways, including ambiguous phrasings that lead to ambiguous answers. Since I want to start off easy, I’ll present only non-ambiguous versions, and I’ll explain the answers.

Problem 1

At the local park, we meet Mr. Smith while his young son plays in the jungle gym. When asked, Mr. Smith says he has two little ones, but his other child is sick at home. What is the probability that Mr. Smith’s other child is also a boy?

The intuitive answer here is the correct one. Here’s the math:

P(2 boys) = P(2 girls) = 1/4

P(1 each) = 1/2

P(observation that a randomly observed child is a boy) = 1/2

P(observation | 2 boys) = 1

P(2 boys | obs) = P(obs | 2 boys)*P(2 boys)/P(obs) = (1)*(1/4)/(1/2) = 1/2

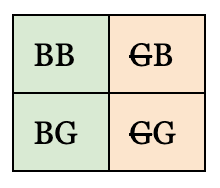

And here’s a visual representation:

If we think of the first letter as the first child observed, that means we eliminated the possibilities of GB and GG, which leave behind BB and BG; the chance of the second kid being male is one option out of two.

Hopefully that makes sense; no tricks, no surprises.

So what’s the paradox?

Problem 2

You and your family want to adopt a couple of kittens, and your son wants one of them to be a boy kitten. A PetSmart employee phones you to let you know that they’ve just come into a couple of Maine Coons. You tell her that one of them needs to be a male. The employee doesn’t know the sex of the kittens, so she puts you on hold and calls the caretaker to ask, “Is at least one a male?” The caretaker responds, “Yes!”

What is the probability that the other Maine Coon is also male?

Here again we have a situation with two young ones, one of them known to be male. The probability that the other one is male should also be 1/2, right?

Let’s check the math. We’ll still be using this equation, same as before:

P(2 boys | obs) = P(obs | 2 boys)*P(2 boys)/P(obs)

But have any of the above values changed?

The probability that both siblings are boys is still 1/2. Conditioned on the assumption that both siblings are boys, the probability that we observe what we observed is still 1. But what’s the probability of the observation itself, the observation that the employee received a “yes” to the question she posed? Out of BB, BG, GB, and GG, there were three options that would’ve led to a “yes”. Therefore:

P(observation) = 3/4

P(2 boys | obs) = P(obs | 2 boys)*P(2 boys)/P(obs) = (1)*(1/4)/(3/4) = 1/3

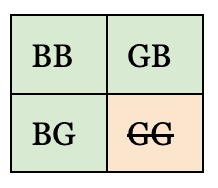

Here’s the visual representation:

The thing to be careful about is this: The way that information was collected is itself information. Different types of random draws will lead to different results.

Note that of Savant’s 17,946 responses when she conducted her survey of readers with exactly two children, 35.9% reported two boys. (Given that human female embryos are slightly less likely to survive, around 51% of births are boys. This would lead us to expect a 34.2% of boy-boy families; I’m guessing that the rest of the difference was response bias, say from readers with boy-boy being more excited to share their status than other families.)

If you’re not feeling 100% solid on the math for these two problems, then let me recommend an additional practice problem: Bertrand’s box paradox (not to be confused with Joseph Bertrand’s other probability paradox, which I will mention again soon, nor his economics paradox.)

Forums

Boy or Girl showed us how the mechanism behind a random “draw” can lead to different results: When asking about the chance that a family before us has two boys, it matters how that family came to be before us. Did we filter out families without Girl-Girl, or did we comes across a family that could have been anything, but then turned out not to have been Girl-Girl? (This is the sort of subtle distinction that’s hard for me to keep in my head without specific examples in front of me.)

For both problems, we started off with the same set of possibilities (BB, BG, GB, and GG) but the probability of our observation changed: 2 out of 4 in one case, 3 out of 4 in the other.

I designed the next set of problems to instead make us question that initial set of possibilities from which all the other probabilities are derived, and will point at another way in which the specifics of a particular “draw” can lead to different results. (And, at least for me, this distinction is actually more intuitive to think about.)

Problem 3

When John was a kid, he used to play in an online roleplaying game that took place on an anonymous message board, where participants would pretend to be the top leaders of various world nations. The message board has long since gone defunct, but fragments of the site have been archived. It’s been so long, John doesn’t even remember the screenname he used to employ, but he does know it was either AnonA, AnonB, or AnonC. Looking at the site’s surviving fragments, John learns that the accounts for AnonB and AnonC were in service of the same country, though that country’s name isn’t visible on the fragment. In other words:

AnonA was a member of Country 1

AnonB was a member of Country 2

AnonC was a member of Country 2

All of these three names seem equally likely to John in memory. What, then, is the likelihood that John was a member of Country 2? Answer in footnote1.

(No tricks; this should be an easy one.)

Problem 4

This messaging board, in order to feel more lively, had some accounts that were controlled by chatbots and others that were real humans. Karissa, who was also a member of this message board, doesn’t remember her screenname whatsoever. She does remember that a member of either Sweden or Finland, and the surviving fragments have shown her that Sweden had one human member, AnonS1, while Finland had two human members, AnonF1 and AnonF2.

Sweden and Finland seem equally likely to Karissa in memory; what, then, is the likelihood that Karissa’s account was AnonF1? FOOTENOTE: Answer: 1/4

(Again, this shouldn’t be tricky. It’s the next one I expect disagreement on…)

Problem 5

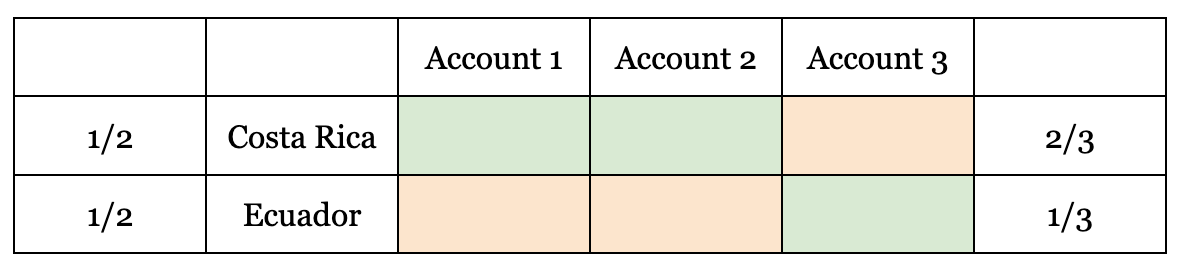

Liam doesn’t remember his country or screenname at all. One of Liam’s friends, who was also in the game, tells him: “You were either a part of Costa Rica, which had 2 members, or Ecuador, which had 1 member. I don’t remember which. I do also remember that one of those two countries was all human and the other one was all bots.” Liam’s friend also shares the screennames of the three associated accounts.

What should be Liam’s belief that he was a member of Costa Rica?

If Liam thinks both countries sound equally likely, as did Karissa, then the answer might be 1/2. If Liam thinks all three screennames sound equally likely, then the answer might be 2/3.

I believe this is an example of Bertrand’s paradox, which Daniel Rubio demonstrates with an example from Bas van Frassen here, but basically says: Probability spaces can sometimes be plausibly divided up different ways.

So what is the correct answer here? If two different ideal mathematical agents were presented this problem, they should both be able to derive the same answer. What would that answer be?

Here’s2 what I think.

Sleeping Beauty

(If you already agree, as I have argued here, that the answer to the Sleeping Beauty problem is 1/2, then you can skip this section and go straight to Problem 8.)

Problem 6

A kidnapper flips a coin to decide how many people he will kidnap.

If the coin flips Heads, the kidnapper will choose one person at random in the entire world to kidnap and lock into an empty cell. On tails, the kidnapper will choose two random people, each of them locked into separate, empty cells.

You find yourself unfortunately waking up in one of these empty cells, and the kidnapper (for whatever reason) explains what he did (and you believe him). First, as a warmup: Should you believe it more likely that the kidnapper kidnapped two people, or only you?3

But now here’s an additional twist: The kidnapper has been inspired by the Sleeping Beauty problem. If the same coin from before flipped Heads, he will force the one person he kidnaps to sleep, wake them up, erase their memory, then repeat 3 times for a total of 4 indistinguishable wakings.

In other words:

Heads: 1 person, 4 wakings

Tails: 2 people, each with 1 waking

Now upon waking, should you believe that the kidnapper more likely kidnapped two people, or only you?4

If you disagree with my answer, then consider this next problem:

Problem 7

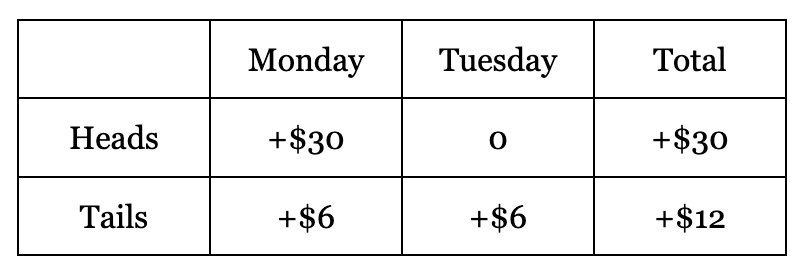

Let’s forget the kidnapper and go back to the Sleeping Beauty problem, but one in which she will be paid for her bother: After every waking, money will be deposited to Beauty’s bank account (without her knowledge). The amount that is deposited depends on the coin flip: On Heads, she will awake on Monday and receive $30; on Tails, she will awake on both Monday and Tuesday and receive $6 each day.

For the first part of this problem, I only ask: If this experiment is repeated many, many times, how many dollars should Sleeping Beauty expect to gain per round on average?5

I have heard the Thirder argument that my answer is the correct answer, yet: During a waking, Beauty should believe the P(H) = 1/3, P(T) = 2/3, and therefore in the moment, Beauty should believe the expected value for her current round is $14. The question I posed is different because it asks about an objective perspective outside multiple runs of the experiment, rather than Beauty’s subjective perspective, and therefore it requires the P(H) = 1/2.

If that sounds correct to you, then I would pose the following variant. Before the experiment begins, Sleeping Beauty is put to sleep like normal with only the usual information supplied to her about the original SB problem. When she awakes, there is a surprise message left for her:

You may agree to play the following game: If the coin had flipped Heads, your bank account will receive $30 right now. If the coin had flipped Tails, your bank account will receive $6 right now. However, once this round of experiment is over and you awake, you will pay $18 for having played this game. (If you are inconsistent between wakings about whether you agree to play the game, the game is considered defunct and all bank transfers will be reverted.)

In other words, the expected value of playing this game for one round is the following:

P(H)*$30 + P(Tues-Mon)*$6 + P(Tues-Tails)*$6 - $18

Let’s also assume that many rounds of this game will happen, so any streaks of bad luck will be canceled out and we don’t have to concern ourselves with Beauty’s risk aversion; she should try to maximize her expected value of dollars gained.

Should Beauty, upon waking, agree to play the game?

If you answered “Yes” to playing the game but “1/3” to the original SB problem, then: How can Beauty meaningfully be said to believe that P(H) = 1/3 if she will not even act on that belief?

If you answered “No” to playing the game, then: After the experiment is completely over and you wake back up into normal life, will Beauty regret having not played the game?

If you answered “Yes” to the previous question, then: Why would Beauty, during the wakings of the experiment, not act in a way to minimize her future regret?

The SIA

Problem 8

Biologists have developed two theories about the finer details of how evolution functions. Theory 2, however, seems to predict that the Earth’s first species with human-level intelligence probably would not have been humans. Rather, Theory 2 predicts that elephants would have more likely spawned Earth’s dominant species, not primates, and resulted in an intelligent lifeform that biologists call elphantines.

Specifically, they estimate:

P(humans | T2) = 1/4, P(elephantines | T2) = 3/4

P(humans | T1) = 2/3, P(elephantines | T1) = 1/3

My first question is this: What should biologists believe is the likelihood of T2?6

Now let’s say T1 and T2 also predict the total number of conscious observers (regardless of whether they’re human or elephantine) that will ever exist on the planet Earth. Say:

P(humans | T2) = 1/4, P(10^15 observers | T2) = 1

P(humans | T1) = 2/3, P(10^12 observers | T1) = 1

My second question is this: Would this change the likelihood of T2 at all?7

Someone who believes in the SIA in the manner of the “presumptuous philosopher” is someone who believes that: Given two theories of the universe, T1 and T2, if all else is equal, then if T2 predicts the existence of N times as many observers (or “observer moments”, e.g. SB wakings) as T1, that implies T2 must be N times as likely as T1. (Which Bentham’s Bulldog, substacker-with-a-following-that-absolutely-dwarfs-mine, uses to argue that the universe must be unequivocally infinite.) With Problem 8, if we simplified the math by assuming a P(humans) = 1/2 conditioned on either theory, then such an SIA believer would predict T2 to be a thousand times likelier than T1.

In Bentham’s example I cite above, he even argues that a theory predicting a trillion times as many observers should be a trillion times as likely.

I struggle to think of anything at all I believe so strongly as that. Maybe something like:

A friend tells me he’s been gifted the ability to see the future. To prove it, he presents a million-sided die and rolls it a million times, correctly guessing which number it will land on every single time.

The chance of my friend having guessed that by random chance would be one in a trillion; after observing such a sequence, I would be absolutely certain that I was hallucinating, my friend had rigged the game, he was telling the truth, or anything else was happening other than him having guessed correctly all those times by getting lucky.

Returning to Bentham’s example:

The physicists discover a mistake in their math. They return to the philosopher and explain: “Sorry: Actually there’s no way T2 can actually be true. T1 is true.”

If that happened, the presumptuous philosopher would have to be absolutely certain that the physicists are lying or mistaken. He would believe they were lying to the same degree I believed my friend wasn’t just getting lucky guessing all the million, million-sided die rolls.

And that, of course, is completely absurd.

The problem with the SIA

I’ve seen the SIA commonly defended in the following two ways:

The SIA is needed to refute the Doomsday Argument.

The SIA works for the God-flipping-a-coin scenario, so it works for other scenarios as well.

I didn’t need the SIA to refute the Doomsday Argument here. But actually I think the second argument gets more to the heart of the matter.

The God-flipping-a-coin scenario goes like this:

God flips a coin to determine whether to make 1 room with 1 person in it, if Heads, or 2 rooms each with 1 person, if Tails. You wake up in a room. What should be your belief that the coin flipped Heads?

The SIA arrives at the answer of 1/3.

You know what else arrives at that answer? Starting with P(observation | Heads) = 1/2 and applying Bayes Theorem.

Theories with more observers or observer-moments being more likely is only true depending on the mechanics of the random draw. Like we saw with the Boy and Girl paradox, different types of draws will lead to different values being plugged into Bayes. More-observers-being-more-likely was true for problem 6. It also happened to be false for problem 4, the Sleeping Beauty problem as well.

It’s possible to believe in the SIA but split with Bentham on the matter of the presumptuous philosopher. Could you have gotten all the correct answers to the problems I presented, using the SIA? I don’t see how.

Maybe I’m wrong. But also, even if it were possible to wield the SIA correctly—does it gain us anything? All the problems I presented can be solved with careful selection of priors and the application of Bayes theorem (which, by the way, is synonymous with saying “the application of conditional probability”, because Bayes theorem isn’t a special law, but rather a rephrasing of other laws). What does the SIA give us that Bayes theorem doesn’t already?

But whatever method you choose to use: Be careful with your assumptions. Probability is hard to get right. Remember that the way information is obtained is itself information, remember that two people with the same knowledge should be able to arrive at the same beliefs, and that two different versions of yourself (say, between memory erasures but also still possessing the same knowledge) should also hold the same beliefs.

I expect that this will be my last post to touch on the SIA and I am finally done with the many refutations of this one argument by Bentham’s Bulldog. I may not be done with anthropics, however. Also: The converse is not the contrapositive. I actually think an infinite universe may be more likely than it’s not! But that may be the topic of another future post.

Bonus: A trap for Halvers

Problem 9

Let’s go back to the Sleeping Beauty problem, but this time Beauty will be sometimes be told what day it is, depending on the coin flip as well as a second coin flip:

HH - told it’s Monday

HT - told it’s Monday

TH - told it’s Monday, then told nothing on Tuesday

TT - told nothing on Monday, then told it’s Tuesday

What is P(first coin Heads) when waking up Mon?

The intuitive answer in this case is the correct one, but do the Bayes math anyway; if you’re like me, you’ll get the math wrong on first try.

Thanks to redditor u/imMAW for this question. Answer is in a comment, to reduce the possibility of spoiler.

2/3

7/12. (Which I think also means that both me and Joseph Rahi were wrong about our fabricated-vs-real-orphanages scenario.)

Two people, with likelihood 2/3

Nothing has changed about the likelihood of whether two people or one were kidnapped; the chance of Heads is still 1/3.

$21

3/11

No.

Answer to problem 9:

P(H1) = P(T1) = P(H2) = P(T2) = 1/2

P(HH) = P(HT) = P(TH) = P(TT) = 1/4

P(Mon | H1) = 1

P(Mon | TH) = 1

P(Mon | TT) = 0

P(Mon | T1) = 1/2

P(Mon) = P(Mon | H1)*P(H1) + P(Mon | TH)*P(TH) = 3/4

P(T1 | Mon) = P(Mon | T1)*P(T1)/P(Mon) = (1/2)*(1/2)/(3/4) = 1/3